Steven Blockmans

Senior Research Fellow, CEPS

The victory of Donald Trump in the 2024 US presidential election may have substantial implications for security in Europe, with particular significance for Ukraine, Moldova, and parts of the Western Balkans. Doubling down on an ’America First’ agenda that deprioritises traditional alliances and reduces US engagement in international conflicts could redefine Europe’s security dynamics, challenging NATO unity and emboldening adversarial actors like Russia, backed up by China, North Korea and Iran.

Casting doubt on US reliability

As the central pillar of Europe’s defence architecture, NATO is likely to experience new tensions under a Trump presidency. During his first term, Trump frequently criticised NATO, questioning its relevance and pressuring allies to increase their defence spending or risk reduced US support. While increased defence budgets among EU member states did materialise, Trump’s rhetoric signalled potential unpredictability in the US commitment to collective security, especially in the event of external threats.

A Trump 2.0 administration consisting of carefully vetted loyalists will cast further doubt on the reliability of the United States in fulfilling Article 5 obligations. This would be especially concerning for Eastern European NATO members, such as the Baltic states, Poland, and Romania, which perceive a direct threat from Russia. If these countries see a potential decrease in US support, it will push them to bolster their own defences and work more through the European Union for security guarantees. The upcoming Polish Presidency’s priority to earmark EU funds for the creation of a so-called ’East Shield’, i.e. military fortifications on the eastern border, fits right into this playbook. Yet, unity within the EU is not guaranteed on these issues, given the blocking potential of the Orbanites.

If Trump’s stance on NATO weakens allied unity and increases divisions within the EU, then it will encourage Russia to expand its role in regions which the Kremlin considers as belonging to its sphere of influence. For Ukraine and Moldova, in particular, a more capricious US foreign policy under Trump will mean a weakened deterrence against Russian influence and aggression.

Creating a vacuum to be exploited by adversaries

The implications of a Trump presidency would be particularly severe for Ukraine, which has relied heavily on US support since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. The Biden administration, along with other NATO members, has provided billions in military, financial, and humanitarian aid to Ukraine, seeking to deter Russian aggression and stabilise the country as it defends itself. During his campaign, Trump suggested that he could end the war in Ukraine swiftly, but it remains unclear what this would entail.

If Trump were to scale back US aid, then Ukraine would face immediate difficulties in sustaining its defence efforts. The depletion of US support would not just undermine morale; it would complicate Ukraine’s military strategy and make it harder to hold its lines against Russian advances. This might pressure Ukraine to negotiate with Russia on terms more favourable to the Kremlin, potentially resulting in a ‘frozen conflict’ where Russia retains control over occupied territories, if not more. Such an outcome would have a long-term destabilising effect on Eastern Europe, with occupied regions serving as potential flashpoints for future landgrabs.

Moreover, a reduction in US support for Ukraine might influence other allies to reconsider their own levels of support, amplifying the consequences of such a policy shift. Although European countries have demonstrated considerable commitment to aiding Ukraine, without the US as a cornerstone backer, it would be significantly more challenging for allies to fill that gap alone.

Moldova too is highly vulnerable to Russian influence and intimidation, as witnessed in the massive but so far unsuccessful attempts at swaying the outcome of two rounds of the recent presidential elections and an EU referendum. Moldova has also faced hybrid warfare tactics, such as cyberattacks and energy blackmail. What’s more, Russia maintains a military presence in the breakaway region of Transnistria. A shift in US foreign policy under Trump will most certainly heighten Moldova’s security risks. The ensuing instability would hinder Moldova’s aspirations to accede to the EU.

The Western Balkans has long been a region of geopolitical contestation, comprising countries that aspire to EU and NATO membership, such as North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, while others, like Serbia, maintain closer ties with Russia. During Trump’s first term, the approach to the Balkans prioritised bilateral deals over a coordinated regional strategy, which at times complicated transatlantic cooperation.

A renewed US retreat from multilateral approaches would create a vacuum for Russia to exploit by increasing its support for pro-Russian entities in the region. This could worsen tensions in Bosnia, where Serb nationalist leaders have repeatedly threatened secession, and in Kosovo, where Serbia has never fully accepted its independence. Trump’s isolationism could inadvertently fuel existing tensions. Additionally, China has been active in the Balkans through investments and infrastructure projects, and any reduction in US involvement which is not filled by the European Union could lead to increased Chinese presence in the region, further destabilising the area’s fragile balance of power.

Misaligned stars

A second Trump presidency will no doubt accelerate the EU’s quest for more strategic autonomy, including increased defence spending and investment in collective security mechanisms. However, achieving European strategic autonomy is not a short-term solution, as it requires significant investment, political unity, and time, all of which are in short supply. In the interim, Trump’s return to the White House could lead to a period of instability in Europe, as countries scramble to adjust to the changing security dynamics and hash out sub-optimal and minilateral solutions to contend with great power politics.

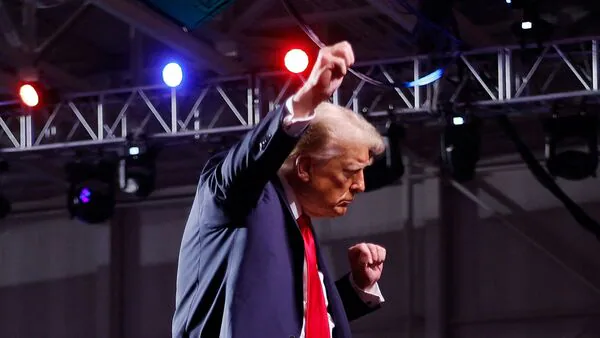

Photo © AP