Julia Friedrich, Polina Lebedeva.

Global Public Policy Institute

Over 1 000 days into the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and at a time when support for Ukraine on both sides of the Atlantic is critically important, it is crucial to consider its long-term implications, including for the Ukrainians living in the 18 per cent of Ukrainian territory currently occupied by Russia. The Russian occupation entails far more than just a change of flags and passports. This much has been clear since Russia first invaded Ukraine in 2014.

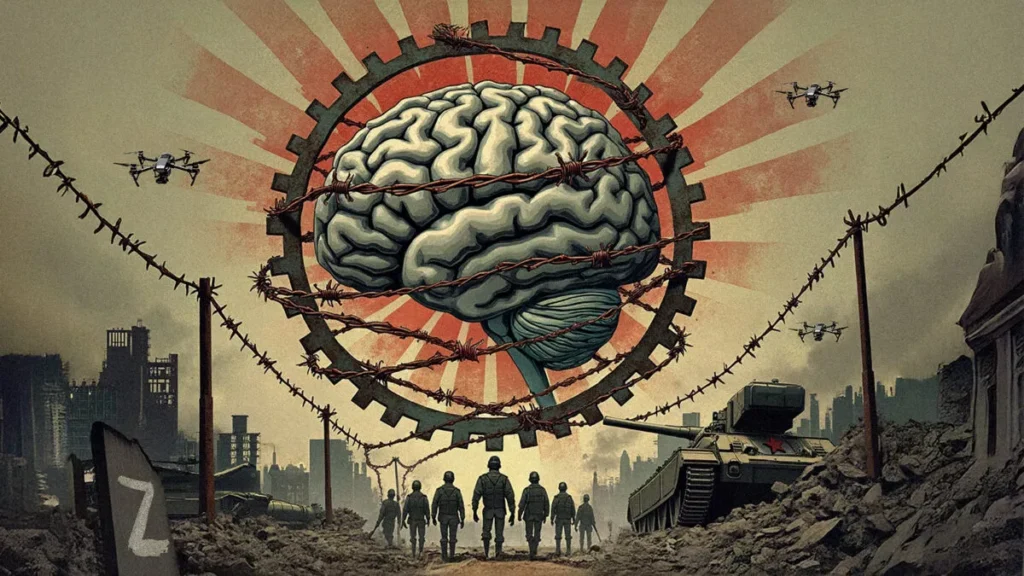

Occupation comes at a tremendous human cost. This is what we discovered in the winter and spring of 2024 during 17 interviews with Ukrainians who were residents from the Kyiv, Kharkiv, Kherson, and Donetsk regions and lived through Russia’s occupation until they escaped or were liberated by the Ukrainian army. Places like Bucha, Yahidne, or Izium became terrible symbols of the war crimes committed there after their liberation. A lesser-known part of the occupation experience is the cognitive violence exercised by the Russian occupiers: the erasure of Ukrainian identity, the use of propaganda, and the attempted occupation of ‘hearts and minds’, all fuelled by deliberate disinformation, which can easily take root in a chaotic information environment. The ensuing sense of hopelessness is instrumental in breaking resistance, getting Ukrainians to comply, and, sometimes, to collaborate, making occupation harder to reverse with every day that Kyiv does not have the means to liberate them.

Information as a lifeline during early occupation

At the onset of occupation, communicating with others and gathering information was both incredibly important and very difficult. For some interviewees, it was not immediately clear that occupation had begun. As hospitals, schools, and other infrastructure shut down almost immediately after Russia launched its full-scale invasion, the same was often true for mobile networks. For some interviewees, getting a signal was a day-filling and dangerous effort and as important to survival as the manual collection of water and food. Where mobile networks did function, disruptions of the electricity supply meant that it could be very difficult to charge phones.

High-stakes decisions people made in the early days of occupation, like choosing whether to stay or attempt to escape, were therefore often based on fragmented knowledge and instinctive reactions. An interviewee from a Kyiv suburb recalled the difficulty of deciding whether to evacuate in this chaotic information environment. While their neighbours urged them to escape, warning that Russian soldiers had already entered their homes, their friends with connections high up in the Ukrainian administration advised against fleeing at that moment.

Where occupation persisted, Ukrainian mobile networks were eventually shut down. An interviewee from Kherson recalled driving across the entire city to see whether their relatives were still alive. After a while, Russian SIM cards were the only way to connect to the outside world – and receive information. In some places, such as Kherson, obtaining these was only possible by handing one’s passport data to the occupiers. Once obtained, a VPN connection was the only means of receiving Ukrainian sources of information.

Hopelessness as cognitive occupation

Crucially, the ubiquity of misinformation and disinformation exacerbated a sense of fear and hopelessness among the population. As one interviewee who experienced the siege in Mariupol told us: ‘People thought the world had forgotten about them.’ This despair could lead to a paralysing of society that was aimed to break any resistance. In the Kharkiv region, one interviewee recalled that they did not follow a relative’s call to flee and join them in Kharkiv because they were convinced that ‘Kharkiv no longer existed.’ Rumours were widespread, fuelled both by the lack of reliable information and deliberate false narratives planted by Russian forces.

This is particularly detrimental given that many of our interviewees stressed that the need to remain hopeful about the occupation’s eventual end was their most important coping strategy – ‘even if it [was] only a small light at the end of the tunnel.’ In the face of false information about the state of the war, this coping strategy becomes no longer sustainable.

Cognitive occupation was part of the same coin as the systematic practices of violent oppression. Physical violence was and remains one of Russia’s main tools of terror. The occupiers systematically kidnapped, tortured, and killed pro-Ukrainian activists and war veterans, as well as anyone suspected of resistance activity. To investigate their targets’ whereabouts, they used prepared lists, city archives, and collaborators’ accounts. A war veteran from the Kherson region shared how they were beaten and electrocuted with a torture device attached to their ears. The back problems and high blood pressure they still experience are bitter reminders of what it looks like to live under Russian rule and what awaits those the occupiers deem a threat to their narrative. The fact that it was their acquaintances who had ratted them out to the occupiers was difficult to shake: ‘[T]he hardest part is when people you’ve known all your life then decide to go for the “Russian world” and betray you.’

Occupying hearts and minds & erasing Ukrainian identity

Where occupation persisted, Russia consolidated its administrative and economic control and intensified efforts to ‘russify’ the local population using material incentives and indoctrination. The most direct form of this ‘russification’ was the occupiers’ pressure on Ukrainians to accept a Russian passport by making access to essential services like healthcare and social benefits almost impossible without one.

Aside from such sticks, the occupiers also used carrots. With limited food supplies, they instrumentalised humanitarian aid as a reward for compliance. Other measures included selling cheap Russian alcohol in sketchy-looking containers, for instance in Kherson, as well as a drastic increase in pensions and sponsored holiday trips to sway the elderly. The latter approach often proved effective, according to our interviewees.

Russia pursued and continues to pursue its objective of eradicating a sense of national identity in Ukrainians and to permanently alter demographic reality in the occupied areas. Using guidebooks (‘metodichky’), Soviet-style posters, and loudspeaker campaigns, Russian soldiers spread propaganda – stating that ‘we came to save you’ – and promising a brave new Russian world. Schools in the occupied areas, many of which were initially closed, later became battlegrounds for indoctrination, with Russian curricula replacing Ukrainian education. The new regime often either intimidated teachers into cooperation or replaced them with unqualified individuals. Workplaces saw drastic changes – one interviewee recounted hiding the Ukrainian flags from occupiers, ‘like the partisans in World War II’. Others collaborated, some out of despair, others out of conviction. Some sought out promotions: ‘Some people who had been selling apples on the markets were suddenly working in high levels of the administration.’ Others felt they had to adapt to the ruling regime eventually.

Erasing Ukrainian identity

By these means, Russian occupiers have successfully pursued their policy to render cultural, economic and political occupation permanent. The longer occupation is allowed to persist, the greater the integration of these territories into Russia – and the harder it becomes to reverse. The same can be true for societal effects, but not in every case. It is tempting to assume that those who remain in the occupied areas today are ideologically receptive to Russia’s policies. After all, many people have escaped. However, as our interviewees reminded us, the decision to flee is far more complex and dependent on a variety of factors such as social ties and relations, the often significant financial cost, and at times the absence of knowledge and information about ways to escape. For those who remain, de-occupation is the only way to live under Ukrainian governance, as Ukrainians, once again.

Fighting cognitive occupation therefore hinges on the hope of de-occupation and a return to Ukraine. Political debates about peace plans are thus inseparable from conversations about the reality of Russian occupation and its consequences for Ukrainians. Any proposal or pressure on Ukraine to freeze the war at its current frontline must confront the human cost of such ‘resolutions’. What might seem like an easier way out or the only feasible compromise politically, is a personal tragedy for those who endured occupation – those whose families have been torn apart or who witnessed war crimes that may never be uncovered. As one interviewee said: ‘It was very difficult to live through all this. I do not wish it on anyone.’

This blogpost is part of a larger study on occupation: “They Came to ‘Liberate’ Us and Left Us with Nothing” – GPPi.

About authors: